A Long Overdue Multi-Part Update

Hello again, friends and supporters. It’s been far too long since I’ve sent an update. It’s been a challenging journey from the point we shipped off the instruments and, if I told you every twist and turn since then, this update would be so long that no one would read it! The short explanation is that I kept hoping there would be a good moment to tell the story without leaving things in the air, but things were just too crazy and busy. Please accept my apologies and promise to do to better.

What I do have for you is an update in multiple parts. The first two parts were written 7 weeks ago, and the last part will catch you up from there. Thanks for bearing with me and I hope you enjoy hearing all about it!

October 28, 2021

I’m writing this on the plane back from Hawaii, after a 48-hour trip where I spent the majority of my waking hours on the summit of Haleakala.

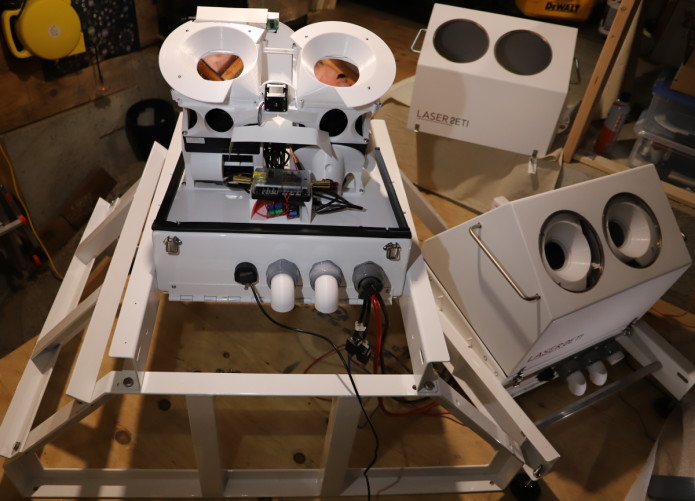

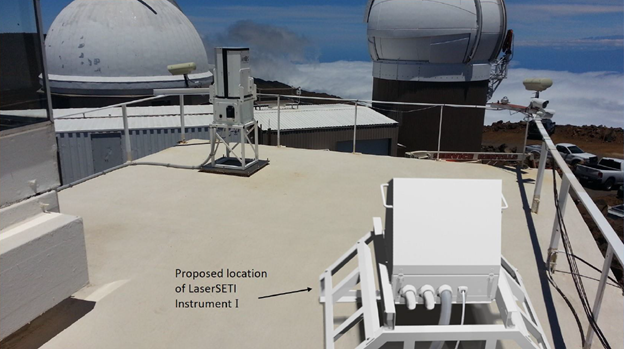

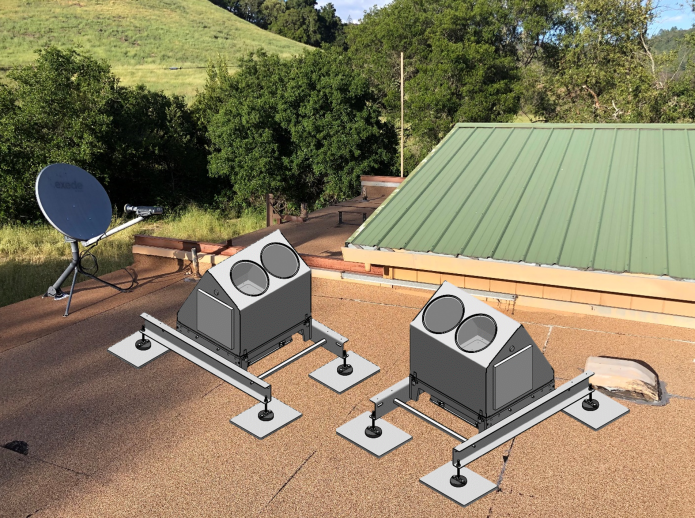

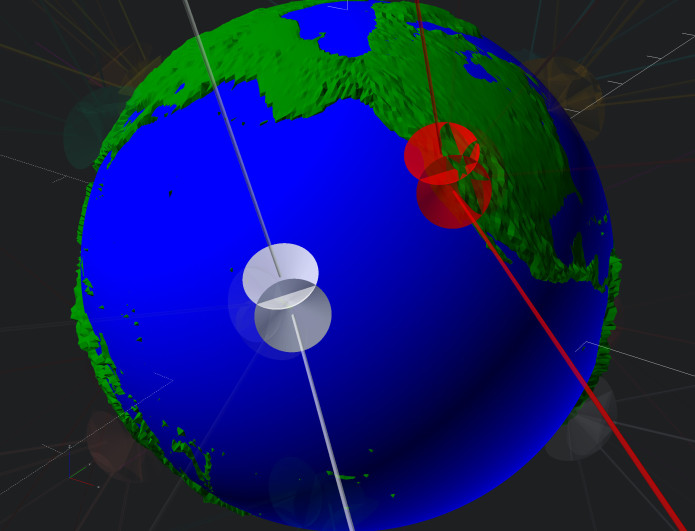

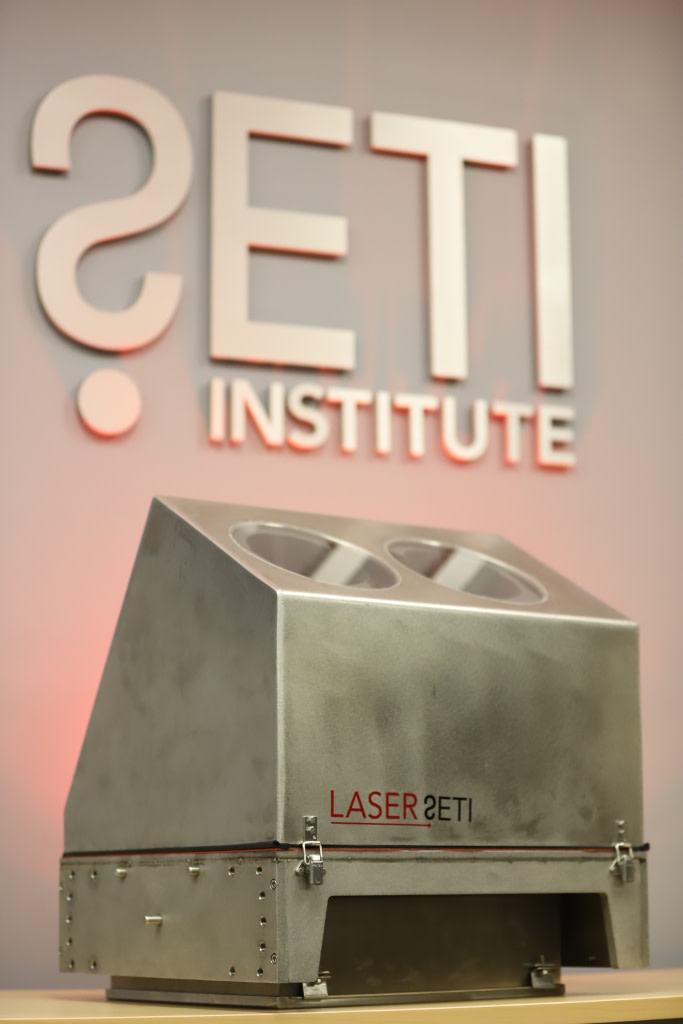

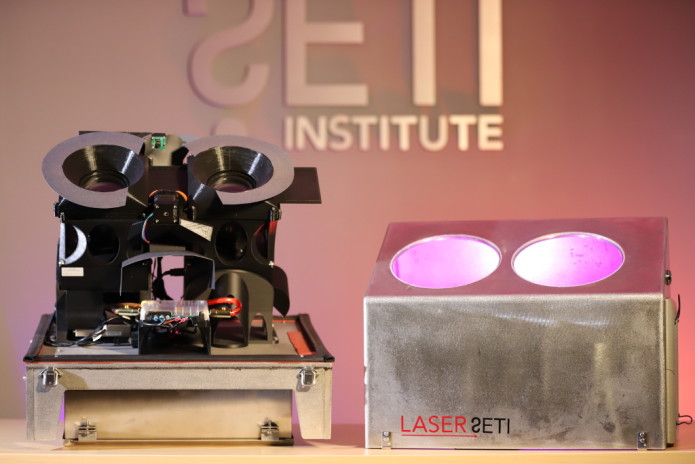

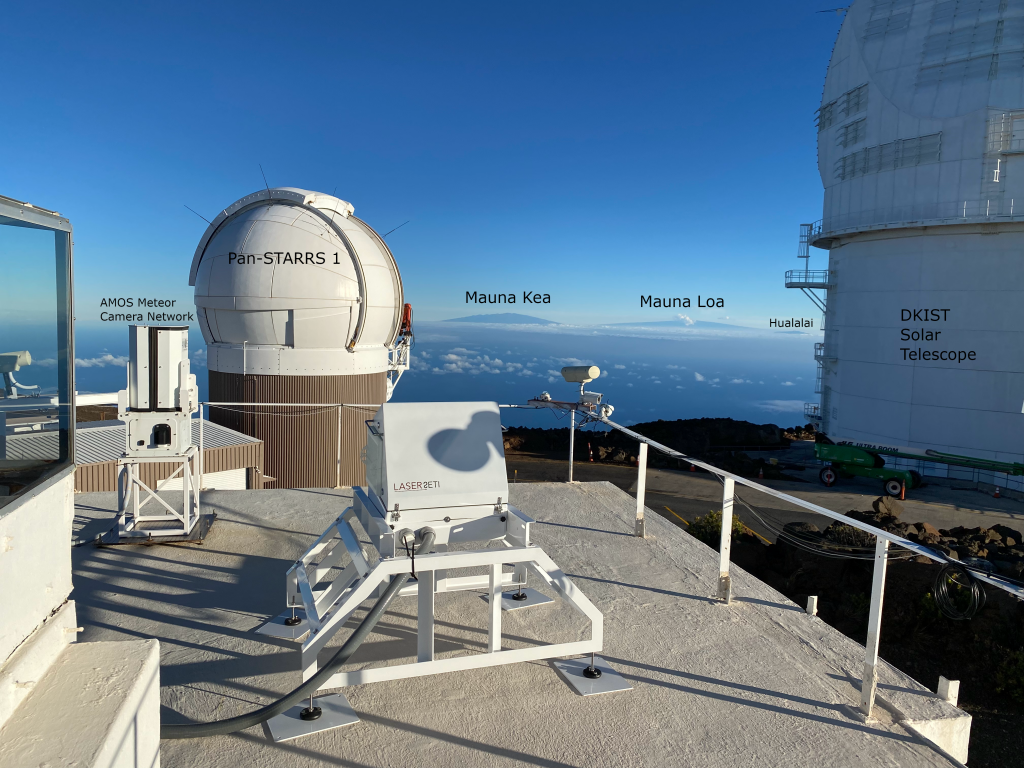

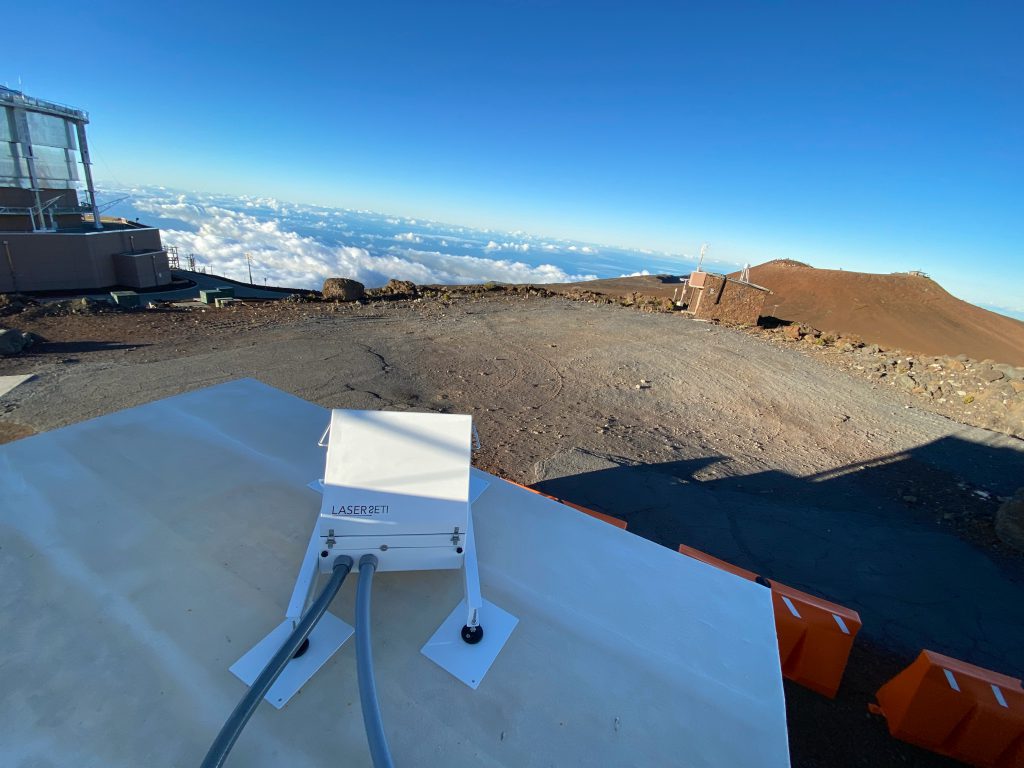

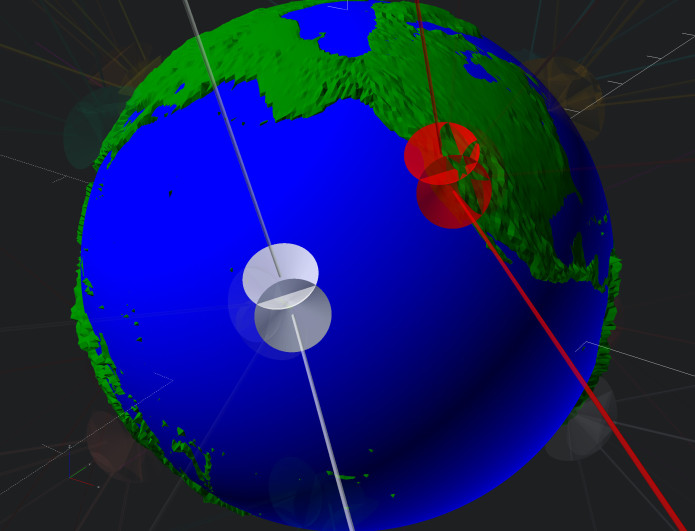

It gives me great pleasure to say that both instruments were installed “successfully” in August, and (I believe) are now working fully. The summit is a stunningly beautiful place, both objectively as well as for astronomy. So, in addition to searching for Near Earth Objects (NEOs) with PAN-STARRS and studying the solar dynamics as never before with DKIST, the Haleakala Observatory will also be searching for technosignatures with LaserSETI!

[Above: IFA2, the southeast-facing instrument, Below: IFA1, the north-facing instrument along with the Air Force’s satellite-tracking telescope is barely visible in the upper left corner]

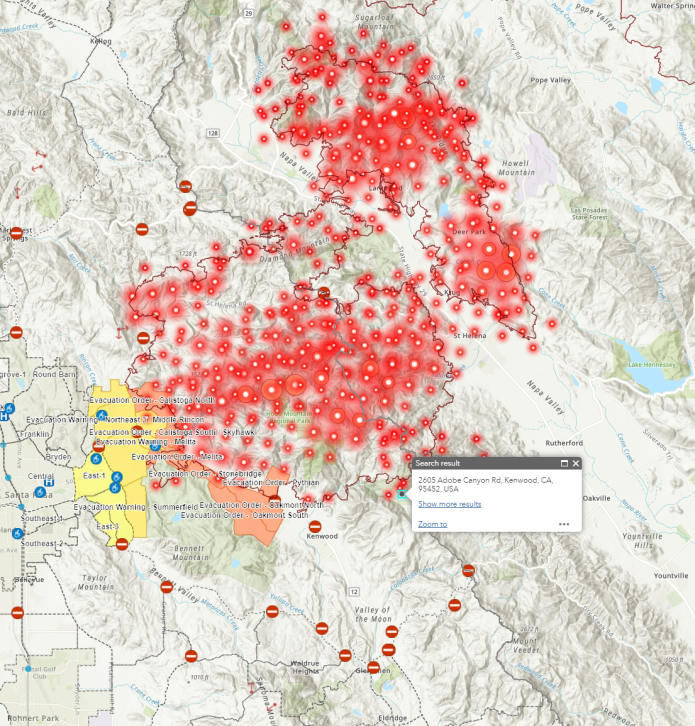

For reference, the instruments at Haleakala look at the same set of stars as the insturments at Ferguson (RFO) in Sonoma, CA.

Knowing how scenic the summit is, we setup a camera to take a time lapse, and the battery almost lasted the whole time.

I’d especially like to thank the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy (IfA) staff, who’ve been very helpful to the project during these difficult pandemic times. Also, as you can see from the time lapse, the setup work was a team effort with the critical help of the SETI Institute’s own Assistant Director Steven Bourdow, as well as my son Jason. It really takes a village to make LaserSETI work, and that couldn’t have been more obvious in the past couple months.

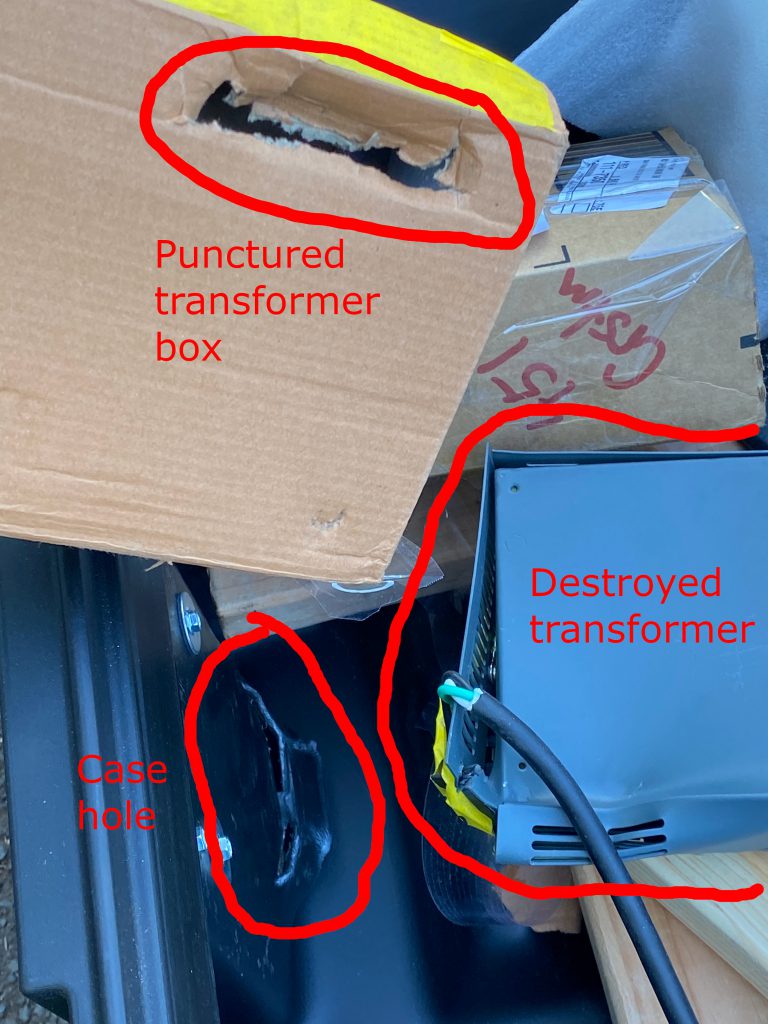

The second half of this update, which details the challenges of the installation, starts with the shipping company puncturing one of the two cases with a forklift, and unfortunately in a way that’s clearly unrelated to intentionally manipulating the case. I found out just before boarding the plane, and when I arrived, I was relieved that they didn’t damage the instruments. But they did skewer the 12V DC transformer that powers everything. “No problem,” I thought, we’ll just order a new one, and I’d purposely planned extra days into the trip precisely in case something went wrong beyond the array of spare parts I’d shipped with the instruments.

The day before I planned to leave Hawaii, after chasing all over East Maui Post Offices, the replacement arrived, and I pulled it out of the box to make sure it wasn’t damaged. I drove it up to the summit, installed it, and powered on our gear. But none of the six exhaust fans worked. “That’s weird, I thought, I tested those a dozen times. And all of them??” As I tried to repair them, fuses kept blowing but I could find nothing wrong with the wiring. A little voice told me to check the input voltage… and it was 24V, double what it should be! Suddenly, in my head, Han was yelling at Chewie “Turn it off! Turn it off!” and I ran to kill the power. The two transformers were identical except for a 12 vs a 24 in the model number. I didn’t notice and apparently neither did Amazon.

It was the end of our last full day, and there was nothing to do but go home. The state of every component in both instruments was in question, and nothing was on the network for me to connect remotely. As I mentioned before, the IfA team is great, so I shipped in a _new_ new transformer and, after carefully checking the model number, they swapped it in. We then did some networking magic to connect into the gear and make it remotely accessible. Finally, I could assess the state of the equipment.

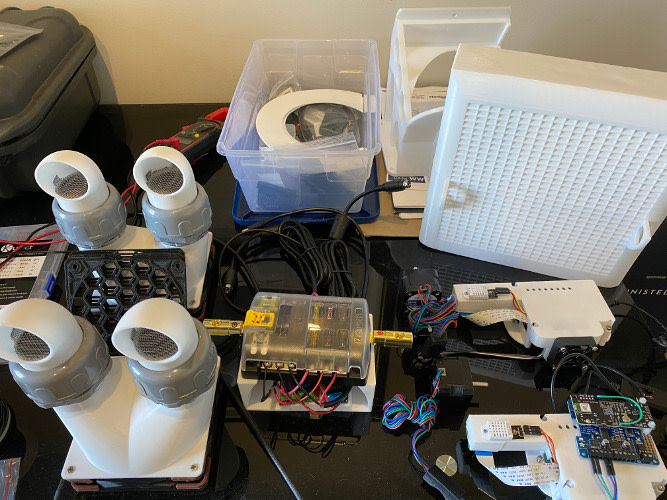

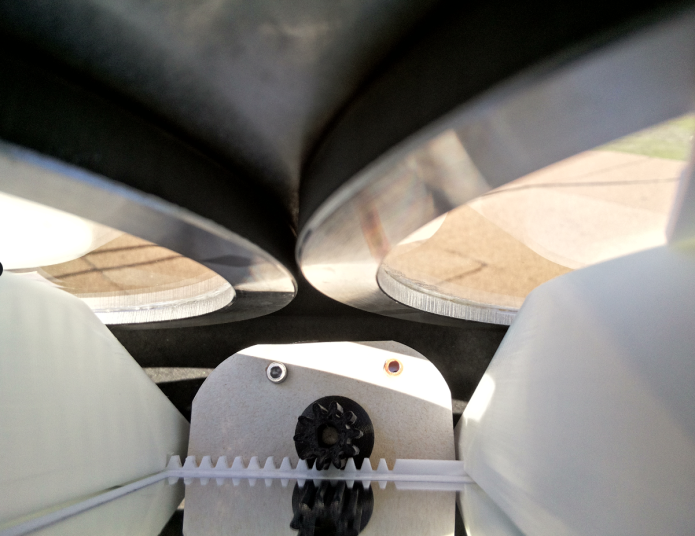

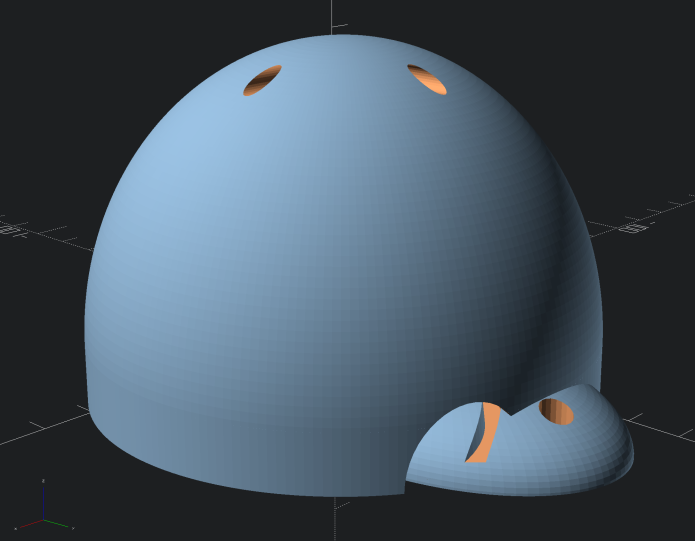

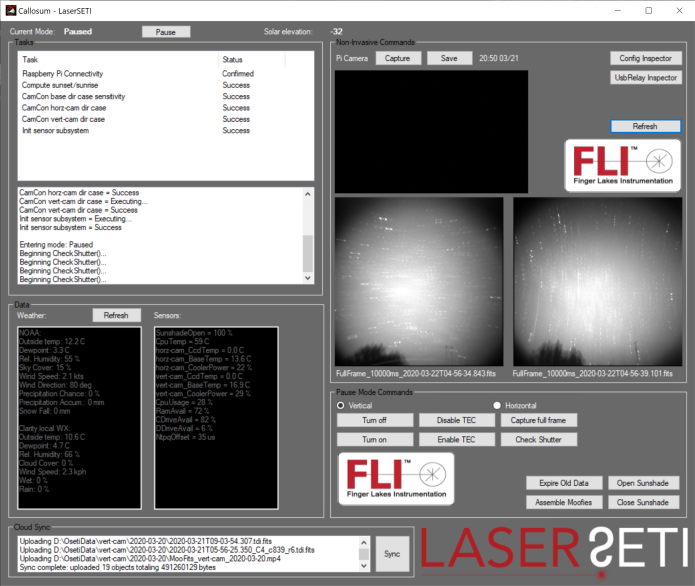

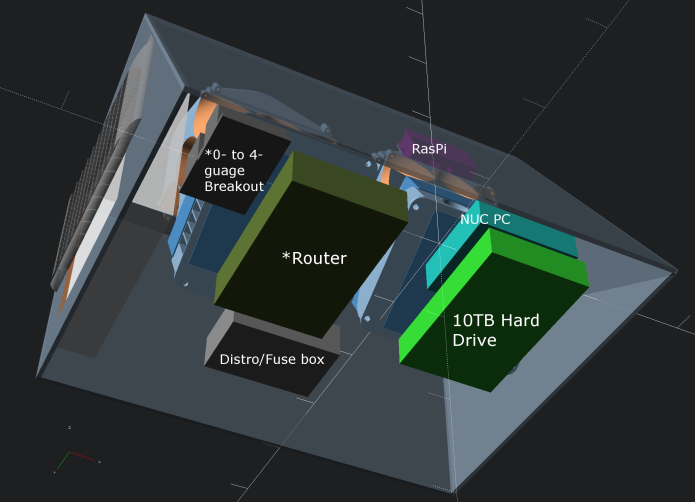

Fortunately, the heart of the instrument, the science cameras passed a whole battery of tests, and the networking and Intel science computers checked out too. The raspberry pi is the central nervous system, with sensors and the motor to open and close the sunshade, which protects the camera shutters from the Sun during the day. One pi was wiggling the motor but not able to open the sunshade, the other pi was offline completely. If we had to be unlucky with this double disaster, at least they were inexpensive components, and also not the router which would’ve made the whole system inaccessible.

Meanwhile, we’re going through the claims process with the shipper who punctured the box to begin with (resolved painfully but satisfactorily) and Amazon (like the Energizer Bunny, it’s still going). We also built new raspberry pi’s, to prepare for complete replacement of the existing ones in both systems. This was more challenging since all our tools and spare parts were in crates still stuck on Maui due to the claims process then a scheduling incompatibility between the shipper and IfA.

And so, in the past 2 days, I swapped out the motor controller boards in both pi’s, focused all four science cameras, and dealt with a couple of other minor issues that cropped up. In addition, our shipping cases should be on their way back to CA, and a new one is being manufactured to replace the punctured one—since we don’t want contaminants or pests taking up residence in the new instruments during the case’s next voyage.

December 17, 2021

More good news and less-good news.

First, the less-good news. When I arrived home in October, the two IfA instruments were performing well. Then, occasionally two of the cameras would exhibit a strange, transient issue that was easy to clear. Then, it started happening more often and not clearing as easily. So I engaged the camera manufacturer to get their advice. Just after I did that, however, the two cameras—one in each of the two instruments, unfortunately—went completely offline, and no amount of Fonzie’s Magic Touch™ could coax them back online for further diagnosis, repair, or workarounds. Adding insult to injury, that’s when severe weather hit the Hawaiian Islands, causing blizzards and more at high altitude. The summit lost power for about 4 days and networking connectivity for 9. Apparently, they had to splice in 200 feet of new fiber a couple miles from the summit, in a spot that was a 3 hour hike to get to, and the first time they tried the equipment didn’t work due to the altitude!

The instruments dutifully came back online earlier this week, with frost covering their windows but that cleared after another day or so. Yet still both troublesome cameras remain offline. At this point, I’m fairly certain we’ll have to use the two spare cameras we’d ordered for the next batch of 10 instruments to swap into the IfA instruments, then hope the camera company can repair the damaged two to replenish our supply of spares.

At the same time, RFO2 (the second instrument at Robert Ferguson Observatory) experienced a similar increasing failure pattern with the hard drive that the instrument writes the camera data to. For a long time, once every couple of months, the hard drive would go offline and require a little software Fonz’ing to get it back. Not ideal, but no big deal. Then, within the span of a couple weeks, it happened more often, then every time we started trying to take data, then anytime we accessed the drive at all. Figuring the most likely cause was the drive itself or the USB enclosure, I ordered replacements and made the 3-hour round trip to swap it in. It looked good at first, but then went straight back into its previous pattern. So I made the trip again, this time with a new USB cable and PC. I swapped in the cable, ran some tests, and everything looked good. Relieved that I didn’t have to perform the hardware and software surgery to swap in a new computer, I went home. That worked great for a couple days, but then it went back to stuck offline. To allow some data-gathering until we can head up there again, I’ve jury-rigged it to write its data to RFO1’s hard drive. The process is intensive enough that single hard drive can’t keep up if both instruments are capturing data, but something is better than nothing, even if just for a short while.

Besides the fact that RFO1 continues to chug along as the Opportunity Mars Rover to RFO2’s Spirit, there’s other good news. After months of claims, almost 100 emails back and work, issues and workarounds, ordering and coordinating, and over 5 weeks in transit (when the outbound journey took barely more than 1 week), on Friday we picked up the cases with our tools and spare parts, along with the replacement case for the punctured one. In addition to closing a long saga, it will be a lot easier to build new instruments and work on the ones at RFO with those! Here’s LaserSETI team member Dan, with our crates loaded up and the punctured one left with the shipper (which they required to settle the claim).

In closing, I just want to thank you all for your support and bearing with us through this difficult year. If we had a dollar for every time things were harder than they needed to be, we could fund the global observatory, but every time I also knew I was blessed to be pursuing this effort on behalf of all of you and that many others had difficulties far worse than anything we experienced.

We will have more news to share soon, but for now let’s just say: Happy holidays to you and yours, and best wishes from all of us at LaserSETI and the SETI Institute!